Achieving Sub-Millisecond Proxy Overhead

Introduction

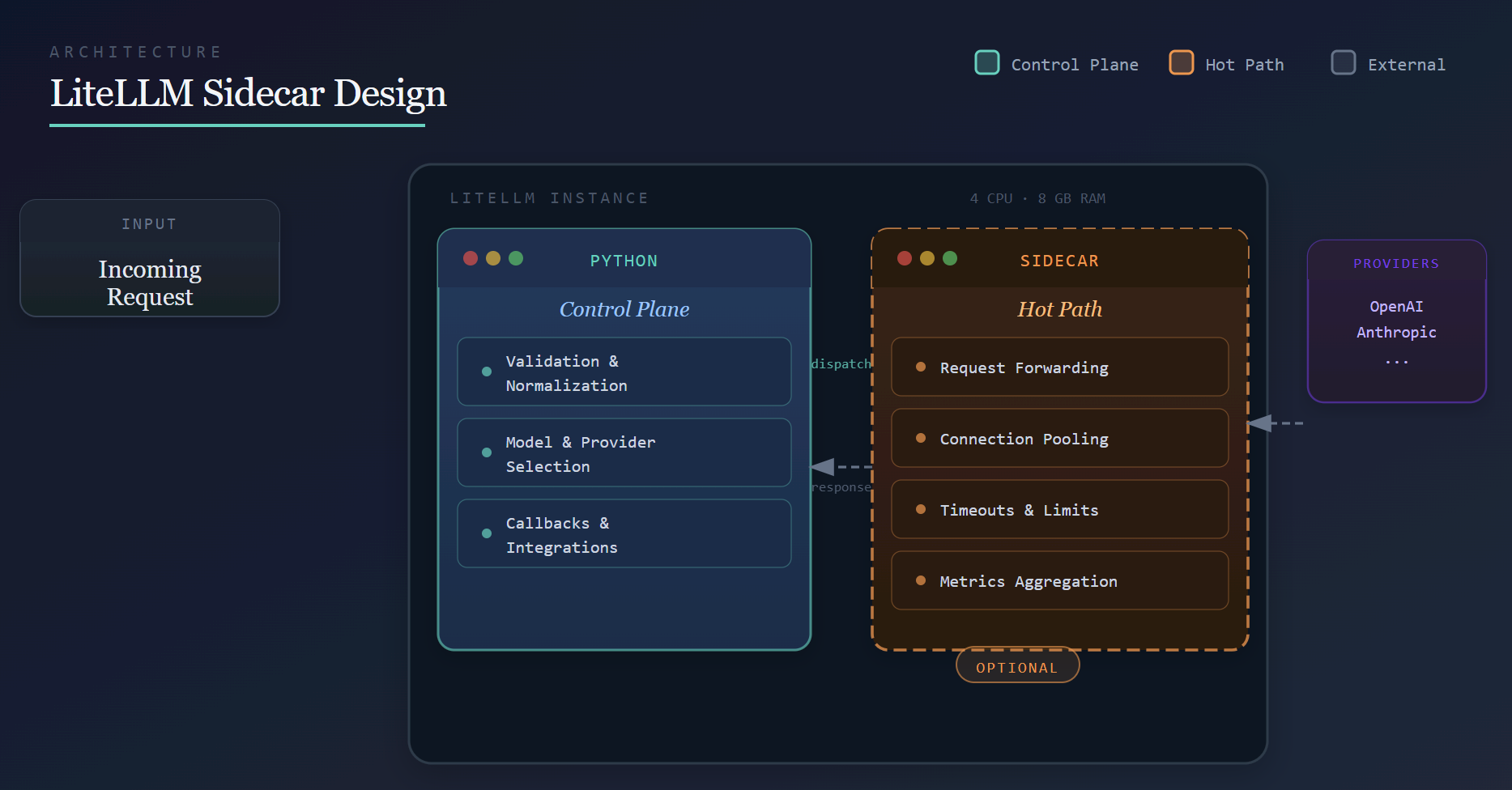

Our Q1 performance target is to aggressively move toward sub-millisecond proxy overhead on a single instance with 4 CPUs and 8 GB of RAM, and to continue pushing that boundary over time. Our broader goal is to make LiteLLM inexpensive to deploy, lightweight, and fast. This post outlines the architectural direction behind that effort.

Proxy overhead refers to the latency introduced by LiteLLM itself, independent of the upstream provider.

To measure it, we run the same workload directly against the provider and through LiteLLM at identical QPS (for example, 1,000 QPS) and compare the latency delta. To reduce noise, the load generator, LiteLLM, and a mock LLM endpoint all run on the same machine, ensuring the difference reflects proxy overhead rather than network latency.

Where We're Coming From

Under the same benchmark originally conducted by TensorZero, LiteLLM previously failed at around 1,000 QPS.

That is no longer the case. Today, LiteLLM can be stress-tested at 1,000 QPS with no failures and can scale up to 5,000 QPS without failures on a 4-CPU, 8-GB RAM single instance setup.

This establishes a more up to date baseline and provides useful context as we continue working on proxy overhead and overall performance.

Design Choice

Achieving sub-millisecond proxy overhead with a Python-based system requires being deliberate about where work happens.

Python is a strong fit for flexibility and extensibility: provider abstraction, configuration-driven routing, and a rich callback ecosystem. These are areas where development velocity and correctness matter more than raw throughput.

At higher request rates, however, certain classes of work become expensive when executed inside the Python process on every request. Rather than rewriting LiteLLM or introducing complex deployment requirements, we adopt an optional sidecar architecture.

This architectural change is how we intend to make LiteLLM permanently fast. While it supports our near-term performance targets, it is a long-term investment.

Python continues to own:

- Request validation and normalization

- Model and provider selection

- Callbacks and integrations

The sidecar owns performance-critical execution, such as:

- Efficient request forwarding

- Connection reuse and pooling

- Enforcing timeouts and limits

- Aggregating high-frequency metrics

This separation allows each component to focus on what it does best: Python acts as the control plane, while the sidecar handles the hot path.

Why the Sidecar Is Optional

The sidecar is intentionally optional.

This allows us to ship it incrementally, validate it under real-world workloads, and avoid making it a hard dependency before it is fully battle-tested across all LiteLLM features.

Just as importantly, this ensures that self-hosting LiteLLM remains simple. The sidecar is bundled and started automatically, requires no additional infrastructure, and can be disabled entirely. From a user's perspective, LiteLLM continues to behave like a single service.

As of today, the sidecar is an optimization, not a requirement.

Conclusion

Sub-millisecond proxy overhead is not achieved through a single optimization, but through architectural changes.

By keeping Python focused on orchestration and extensibility, and offloading performance-critical execution to a sidecar, we establish a foundation for making LiteLLM permanently fast over time—even on modest hardware such as a 1-CPU, 2-GB RAM instance, while keeping deployment and self-hosting simple.

This work extends beyond Q1, and we will continue sharing benchmarks and updates as the architecture evolves.